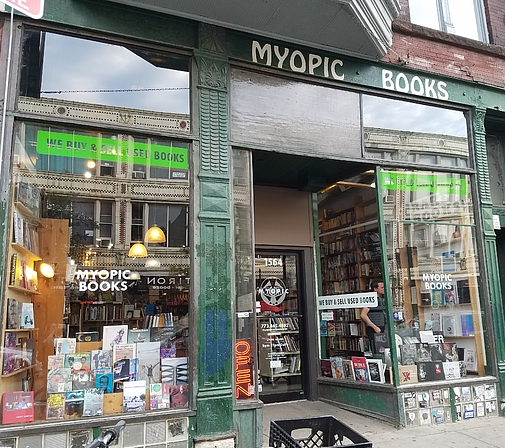

A few years ago, I brought my daughter with me to Chicago, which is where I see friends, try to stay in posh hotels for free, walk around in a city, go to the symphony, and get my hair cut. The place where I get my hair cut happens to be next to a very good used bookstore, Myopic Books, so I left my daughter to go roam around the bookstore while I had my semiannual conversation with the woman who cuts my hair.

When I was done, and I’d heard about the hairdresser’s ambition to leave her job and work in prison justice, I went over to Myopic: no sign of my daughter. I figured the odds of foul play were low, so I started looking around the top floor, where I don’t often go, and found the theatre section.* There among the plays was Letters to Olga, which I hadn’t known existed, also some of Havel’s plays, which I hadn’t read. I knew who he was, of course, but I knew him as the Velvet Revolution president, not as a playwright.

I bought both and started with the letters, because I like letters. A lot. Not to spoil the fun, but I nearly put down the book, because honest to God, he’s a real pill. Which I felt terrible about feeling, because, you know, there he is, a political prisoner, but my God, the way he keeps going after his poor wife, and the hypochondriacal minutiae, and this went on for nearly a year. And then he settled in to work, just as every writer imagines he or she will in prison, and it’s magical. Absolutely stupendous. I won’t ruin it any more than that; you should read these yourself.

The longer I read, though, the more I thought about the silent woman receiving these long, dense, often turgid letters, full of so much hectoring and jealousy, so many accusations about not writing back and attempts at steering her, and in the silence meeting the hectoring I started to feel like she was having a lovely quiet break from the guy. I began really to feel sorry for her, and to root for her — I mean even if she really did mean to read the letters, he just wrote so much — I was imagining her opening a letter, getting about halfway through his philosophical wanderings and complaints, and putting the letter down, sincerely meaning to finish it — and next thing you know, there’s another letter. And another. An another. Until there was a little pile of letters on the counter, just sitting there indicting all the time: you haven’t read me, you haven’t written back. And meanwhile life’s going on, the world’s sliding into the ’80s, Reagan’s become president, John Lennon’s been shot, friends are leaving Czechoslovakia, and time’s moving much faster than it is for the prisoner, and bearing Olga and everyone else away.

As I got near the end I was sitting reading on the bus, and thinking more about time, about the weight of it, those four years, with letters arriving every week or so. Of a mind like that in prison and writing those letters for four years while the world slides away. We talk a lot about prison; we don’t talk about the substance of the years, the weight and meaning of the span, and “prison” in the last decade or so is not so much about dissidents, about muzzling. Which seemed timely again. So I thought: to feel it, you’d have to live it. You’d have to get these letters every week for four years.

That’s a piece of theatre, of course, so I got off the bus and called a friend who has a theatre in Chicago, Theatre Y, which does a lot of Eastern European work, and said, well, what do you think of this, and she said, we have to do this. And so we are. Hugh Ferrer at the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa very sensibly pointed out that there are copyrights involved, so I got in touch with Paul Wilson, who translated not only Havel’s letters but much of Havel’s writing and many other Czech dissident writers’ work, and asked him what he thought of it; he said he liked the project fine, and gave permission. (And yes, if it goes beyond this we will of course have to look for permission from whoever owns the property now — my copy’s Holt, so MacMillan or the German parent.)

So there we go. After that there was a lot of thinking to do about how exactly to make this go, how to send the letters — in the end I’ve typed them on my old Olivetti and old typing paper, and since mimeos are expensive now I’ve repurposed a broken old laser printer and am using the flimsiest stock I could find, and copy them, then mail them out. Who to? I canvassed friends I thought might be interested in receiving these letters for four years — artists, writers, playwrights, arts advocates, political-science people — and asked them simply:

1. Receive and read the letters for the four years.

2. Please don’t read ahead.

3. Pass on the letters to at least one person.

4. At the end — “end” loosely defined — make something informed by the experience. Collaborate, don’t collaborate, do as you please.

That is it. It’s happening, of course, in the context of our own political teetering. I had actually been going to wait till next year to start — everyone’s exhausted, the pandemic’s stretching everyone — but I thought the timing demanded we start now. So — there we are.

I do the blogging, but others on the project might, too.

Questions, just drop me a line on the contact page.

amy

*the kid is fine, though I can’t remember now what books she walked out with. I’ll have to ask.